Merry Christmas everyone!

Unlike last year, this year i'm glad i managed to hold on to my "traditional christmas special release" - so, here it is, this year's "Christmas Shinkansen": the first mini-shinkansen and one of my actual favourites - the 400 Series!

From left to right: original livery, 6-cars formation (1992-1995) and the 7-cars formations in the old (1995-2001) and new (2001 to 2010) liveries.

Already available on my website!

As we all know well, the Japanese Shinkansen is special among high-speed railways, as it is entirely confined within it's own infrastructure, to the point of being conceptually inseparable from it: a new Shinkansen services equals directly the construction of new Shinkansen infrastructure. This is in contrast with "European" high-speed rail systems, where this correlation between the "train" and it's "infrastructure" is a bit more fuzzy, as high-speed trains are able (and the whole network was designed with the intent) to run both on dedicated high-speed railways, as well as conventional railways, either on approach to the "historic" city-center stations, or on the "outer parts" of their services, where construction of a dedicated high-speed railway line is considered unsuitable due to higher costs in comparison to perspective revenue earnings (for instance, within the German ICE system the correlation between "train" and "infrastructure" is even almost entirely nill).

This is a double-edged sword - on one hand, with a system that entirely requires it's own infrastructure, it is definitely harder to "half-ass" the extension of high-speed railway services, from both a political as well as technical-economic perspective: high speed "farces" where an high speed train only runs on conventional lines, or for only a minimal part of it's journey (while retaining the same fare price as "normal" high-speed trains) are nearly impossible to do with a Shinkansen-style system.

On the other hand, you still cannot "half-ass" extension, wich means that medium-sized towns and places that have the potential demand for an improved, high-quality and fast Inter-City service need to be excluded

a priori

as building the completely segregated infrastructure carrying these services would not make any economic sense, with construction costs potentially never recouped by ridership revenue, not even in the very long term.

This problem, or better, inherent limitation of the system, was already well understood by JNR engineers working on Shinkansen planning togheter with the national and prefectural governments.

The choice of a completely segregated infrastructure was of course a foreced one: there was simply no (safe) way to attain high-speeds on 1067mm gauge tracks: adopting any other track gauge would've obliged the construction of an entirely new "network", completely segregated from the main "conventional" one (to this end, the shinkansen could very well be even broad-gauge, the result would've been the same).

To address this, more specifically the issue of "how do we bring quality higher-speed services to towns and places that do not warrant the construction of an entirely dedicated new Shinkansen line", JNR engineers dabbled into the "Super-Tokkyu" concept between the 1970s and the early 1980s: the idea was instead to extend the Shinkansen, to straighten and upgrade to near-Shinkansen standards (and predisposing them for an eventual long-term conversion to full-Shinkansen standard) sections of the existing 1067mm narrow gauge lines, allowing for specially-designed limited express trains (or "upgraded" standard ones) to reach up to 160Km/h on them, allowing higher speeds than conventional limited express trains, while being able to run for the rest of the journey on normal "conventional lines" at "normal" limited express speeds.

The concept unfortunately never fully saw the light of day, as the planned lines were curtailed one after the other, due to budgetary constraints - only the Hokuetsu Express line, with it's former 160Km/h service speed exists as a "spiritual heir" to the concept.

The idea was sound, if not intruiging , but at the time, due to the poor financial status of JNR, it was relegated to the bottom of the priority list. Only after JNR's privatization in 1987, the issue of extending Shinkansen services outside their specially-built infrastructure the issue resurfaced again: by then all major cities whose passenger demand warranted (or made economically viable) the construction of an entirely segregated infrastructure had been connected, or were being connected, with said infrastructure being under construction.

In particular, Yamagata city, with it's population of roughly 250'000 residents, was increaingly, and vociferously asking for an improved and direct connection to Tokyo, then only handled either by the "Tsubasa" limited express trains, with a meager five daily rountrips between Yamagata and Fukushima (where passengers were supposed to transfer to the Shinkansen, for a total of three hours and nine minutes of travel time) or by the daily Akebono sleeper train, an option that was rather impractical.

The final impetus towards serious consideration for a Shinkansen service to Yamagata came in the mid-1980s, as the city was selected to host the 47th "National Sports Festival" (a sort of "domestic olympics"-type of event), scheduled for 1992.

Plans to get a Shinkansen-style service to Yamagata actually had existed for some year in the form of Mr. Suichiro Yamanouchi's (JNR's manager for north-of-Tokyo lines, and soon after, vice-president of the newly formed JR East) musing and notes: inspired by the french TGV practice, he first drafted the first concepts to extend Shinkansen services onto conventional lines in 1983, with Yamagata city as case-study (the rationale being to serve the popular skiing resorts of the area). Depsite some interest from fellow colleauges, wich helped with detailed drafting and planning for the Yamagata extension, the plan was ultimately rejected by JNR's higher-ups, as privatization loomed. The project finally gained serious traction after bypassing the JNR upper management entirely, as Mr. Yamanouchi presented his plans to diet representatives and other elected officials from Yamagata prefecture, wich were enticed by the idea.

Using the scheduled sports festival as leverage, the "Yamagata Shinkansen" project finally got the go-ahead in 1988, as funding was reluctantly granted by the Ministry of Finacnes, wich remained rather skeptical of the concept overall. In the same year, the newly-formed JR East and Yamagata Prefecture decided to jointly fund the extension, rahter than leaving the whole burden on the national government, by forming a special ad-hoc company: "Yamagata-JR Direct Express Holdings", tasked with being essentially a funding "piggy bank" for infrastructural works, and the owner of the rolling stock to be used on the line (to be brought jointly by JR East and Yamagata Prefecture, and to be leased to the former for normal operation).

In actual infrastructural terms, Mr. Yamanouchi's TGV-inspired solution was essentially the opposite of the old "Super-Tokkyu" concept of 1970s JNR: instead of bringing "conventional lines" to near-Shinkansen standard, the idea was to have Shinkansen trains run on actual conventional lines, with little or minimal alignment alterations. This of course posed a handful of issues, due to the need to somehow interface a network with a wide loading gauge, 25'000v AC 50Hz electrification and, most importantly, 1435mm standard gauge, with a narrow loading gauge network with 20'000v AC 50Hz electrification (in Yamagata's case) and 1067mm gauge tracks.

The solutions were essentially pragmatic: 1435mm gauge prevailed - the conventional lines would've been re-gauged to 1435mm (while retaining local services, in the form of adequate electric multiple units built for or adapted to standard gauge). For the loading gauge it was instead to be the opposite: the narrow 1067mm gauge was to be retained (as enlarging tunnels and adapting the rest of the infrastructure to the Shinkansen's wide loading gauge was extremely expensive) with the inevitable "gap"at "full-Shinkansen" platforms to be filled by retractable steps. Electrification was the one that actually posed the least amount of problems: the new Shinkansen trains would've been just multi-voltage sets.

Dubbed "Mini-Shinkansen", construction works, chiefly the regauging of the Ou Mainline between Fukushima and Yamagata to standard gauge, began in late 1988. At around the same time, the first concrete steps were undertaken in regards to the construction of the extension's special rolling stock.

It's here that we finally see the birth of the 400 Series, the first entirely new Shinkansen design of the newly-formed JR East.

Being a train planned to fit the same loading gauge of conventional trains, the 400 Series used the 20m bodyshell lenght and 2945mm width rather than the Shinkansen's 25m and 3380mm respectively. Trains were to be formed of six cars, to be coupled to longer 200 Series trains (running

Yamambiko services) for the leg of the journey on the Tohoku Shinkansen, between Fukushima and Ueno.

As such, the 400 Series had to be designed to be entirely compatible with it's JNR-era brethen, and thus had to fetaure a handful of slightly obsolete technical fetaures, such as a thyristor-phase traction control.

[continues in following post]

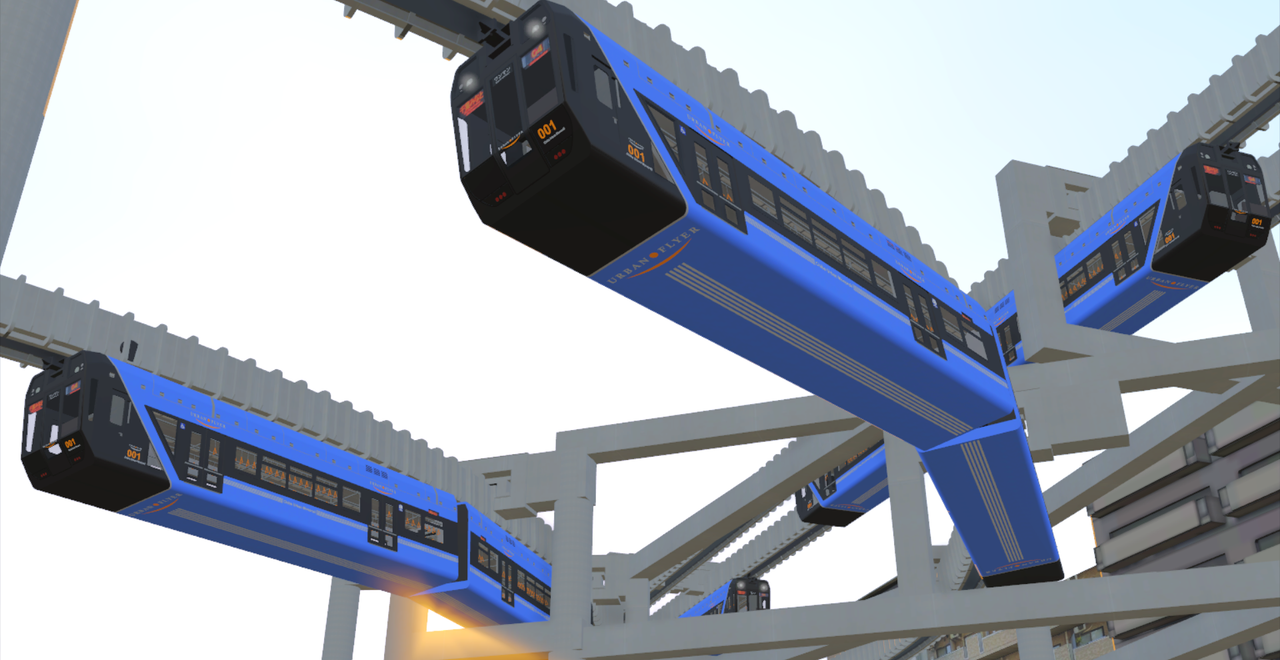

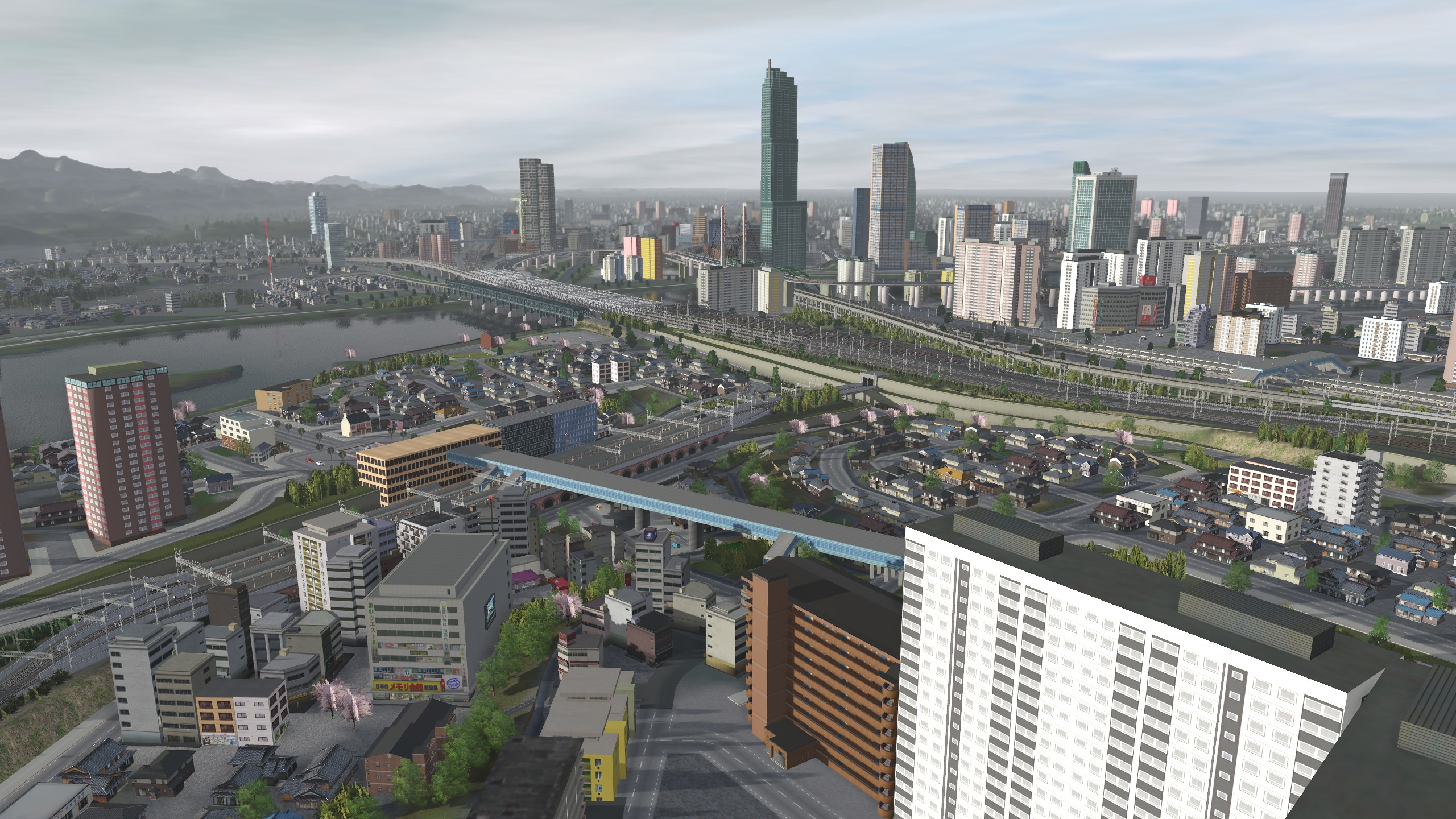

TRS19_2023_11_13_23_11_52_463 by pagroove, on Flickr

TRS19_2023_11_13_23_11_52_463 by pagroove, on Flickr TRS19_2023_11_13_22_53_02_717 by pagroove, on Flickr

TRS19_2023_11_13_22_53_02_717 by pagroove, on Flickr TRS19_2023_11_13_23_34_23_432 by pagroove, on Flickr

TRS19_2023_11_13_23_34_23_432 by pagroove, on Flickr TRS19_2023_11_13_23_27_40_485 by pagroove, on Flickr

TRS19_2023_11_13_23_27_40_485 by pagroove, on Flickr TRS19_2023_11_13_23_29_08_150 by pagroove, on Flickr

TRS19_2023_11_13_23_29_08_150 by pagroove, on Flickr TRS19_2023_11_13_23_38_38_908 by pagroove, on Flickr

TRS19_2023_11_13_23_38_38_908 by pagroove, on Flickr