rcwarner1953

Gandy Dancer

Table of Contents

2025_01_11 *** New ***, Iron Ore Granger Railroads

2024_11_15 GLIO Roundhouses, Part 2

2024_09_01 GLIO Roundhouses, Part 1

2024_06_07 Tower Soudan Mine Tours & other

2024_05_08 Hot Boxes

2024_04_23 Ore Dock and Yard Operations, Part 2

2024_04_09 Ore Dock and Yard Operations, Part 1

2024_03_29 Pulpwood

2024_05_18 Ore Cars and Ore Trains

2024_03_08 GLIO Introduction

GLIO Introduction

This is the start of a blog about various railroad topics using the GLIO as an example. Questions and comments are welcome.

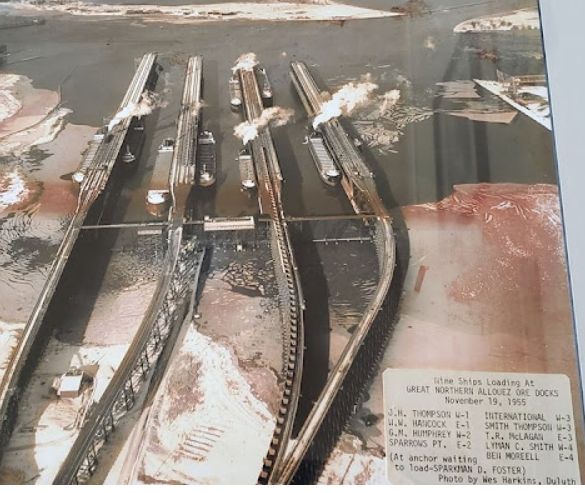

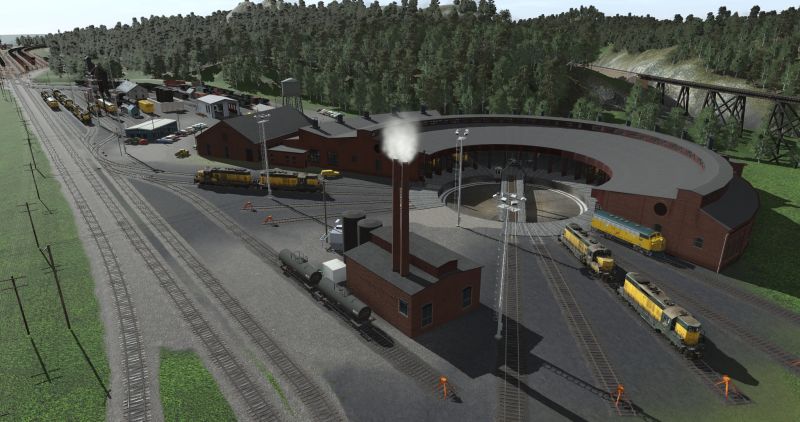

The GLIO is my first route. I missed my railroading days and thought to build my own railroad to enjoy. Because I actually had railroad experience, it would be as real world as I could make it. The starting idea was to build a route that I could run many different types of trains. I, as a child and adult, was always fascinated by the iron ranges of Minnesota and the operations on the ore docks of Duluth, MN and Superior, WI. The route would have an iron range, with mines, collection yards, sidings, etc. The port would have an ore dock, sorting yard, roundhouse, etc.

There are at least three factors to consider when building a railroad. What type of railroad would this be? The answer, it will be built for heavy trains. It is not a glorious trans-continental high speed mainline. The other two factors interact with each other. Construction costs vs operating costs. Flat and curve less track means cheaper operating costs. The decision, after an initial fictional survey, would be to build a mainline from the collection yards to the docks and to not have long uphill grades of more than .5% and short downhill grades of 2%. In the diesel DC traction motor era, the rule of thumb is 1 hp per 1 ton per 1% grade. Four EMD F-7s, 1500 hp each, should be able to pull 12,000 tons. Roughly 120 ore cars.

The considerations to build track to the mines is different. Mines open and get depleted and then close. The goal is to get to the mine cheaply. Higher operating costs are OK.

My goal was to also make enough scenery changes to make it interesting. The Missabi iron range is part of a large geological uplift, hence the various rock features. The marshes and forests are a predominate feature around Lake Superior which I feature around the mines. The trees are primarily quaking leaf aspen which has replaced the old growth pines cut down in the 1800’s. I tried to help GPU loads by using lakes, fields, cut timber areas. There is some small-scale farming in the Great Lakes area. I also used many railroad building construction practices to keep the .5% grade, fills, cuts, horseshoe curves, and tunnels.

As it turned out, the route's hardest sustained pull for a loaded ore train is coming into the Hillcrest siding. The Soo Line had a 20 mile .5% hill from Genola, MN to Onamia, MN. This branch line was mostly used for grain trains to the ports of Duluth and Superior. The trains were always at the maximum tonnage for the horsepower used. Being really bored, I would get off the caboose and run behind the train. That is the reality of bulk tonnage railroads.

Enough for now.

Gandy Dancer

2025_01_11 *** New ***, Iron Ore Granger Railroads

2024_11_15 GLIO Roundhouses, Part 2

2024_09_01 GLIO Roundhouses, Part 1

2024_06_07 Tower Soudan Mine Tours & other

2024_05_08 Hot Boxes

2024_04_23 Ore Dock and Yard Operations, Part 2

2024_04_09 Ore Dock and Yard Operations, Part 1

2024_03_29 Pulpwood

2024_05_18 Ore Cars and Ore Trains

2024_03_08 GLIO Introduction

GLIO Introduction

This is the start of a blog about various railroad topics using the GLIO as an example. Questions and comments are welcome.

The GLIO is my first route. I missed my railroading days and thought to build my own railroad to enjoy. Because I actually had railroad experience, it would be as real world as I could make it. The starting idea was to build a route that I could run many different types of trains. I, as a child and adult, was always fascinated by the iron ranges of Minnesota and the operations on the ore docks of Duluth, MN and Superior, WI. The route would have an iron range, with mines, collection yards, sidings, etc. The port would have an ore dock, sorting yard, roundhouse, etc.

There are at least three factors to consider when building a railroad. What type of railroad would this be? The answer, it will be built for heavy trains. It is not a glorious trans-continental high speed mainline. The other two factors interact with each other. Construction costs vs operating costs. Flat and curve less track means cheaper operating costs. The decision, after an initial fictional survey, would be to build a mainline from the collection yards to the docks and to not have long uphill grades of more than .5% and short downhill grades of 2%. In the diesel DC traction motor era, the rule of thumb is 1 hp per 1 ton per 1% grade. Four EMD F-7s, 1500 hp each, should be able to pull 12,000 tons. Roughly 120 ore cars.

The considerations to build track to the mines is different. Mines open and get depleted and then close. The goal is to get to the mine cheaply. Higher operating costs are OK.

My goal was to also make enough scenery changes to make it interesting. The Missabi iron range is part of a large geological uplift, hence the various rock features. The marshes and forests are a predominate feature around Lake Superior which I feature around the mines. The trees are primarily quaking leaf aspen which has replaced the old growth pines cut down in the 1800’s. I tried to help GPU loads by using lakes, fields, cut timber areas. There is some small-scale farming in the Great Lakes area. I also used many railroad building construction practices to keep the .5% grade, fills, cuts, horseshoe curves, and tunnels.

As it turned out, the route's hardest sustained pull for a loaded ore train is coming into the Hillcrest siding. The Soo Line had a 20 mile .5% hill from Genola, MN to Onamia, MN. This branch line was mostly used for grain trains to the ports of Duluth and Superior. The trains were always at the maximum tonnage for the horsepower used. Being really bored, I would get off the caboose and run behind the train. That is the reality of bulk tonnage railroads.

Enough for now.

Gandy Dancer

Last edited: